An enzyme that makes the male sex hormones has unravelled a fresh clue about how snail shells come to be curly.

It’s a new twist on how scientists thought snails and molluscs develop and form their distinctive whorly shells.

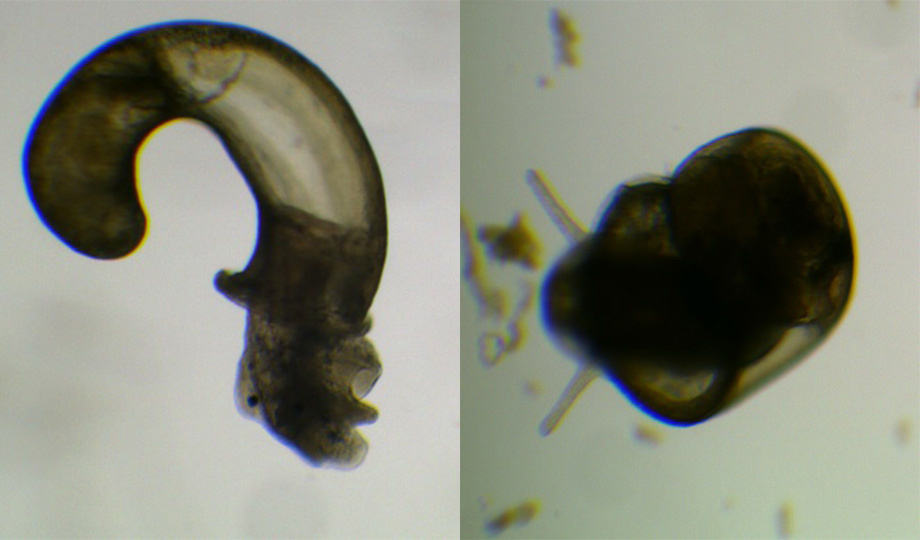

5-alpha-reductase (5αR) is the enzyme humans use to convert hormones needed to reproduce. Researchers turned off that same enzyme in developing snails and found their snails grew banana-shaped shells instead of spirals.

“Normally they look like ramshorn shapes, very tightly curled,” said Dr Alice Baynes at Brunel University London. “But here they get very elongated, so something’s happening when we disrupt their 5αR”.

“We’re not sure if not having the enzyme stops the shells from curling, or if the curl isn’t starting at the right angle. The enzyme is probably converting something into a hormone that helps shell patterning. They just get this really wide-open curl and when they keep growing for longer, their shells actually look like ring donuts.”

In mammals, 5αR converts the male sex hormone testosterone into the stronger male sex hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT), an androgen which helps male development and reproduction. Snails and molluscs, like mussels and squid, also have the 5αR enzyme. But research shows that snails do not use either testosterone or DHT for reproductive development. So scientists wanted to discover what snails do use these hormones for.

In a study in Nature’s latest Scientific Reports, the team used the drug dutasteride – which treats enlarged prostates – to block 5αR enzymes in growing snail embryos.

“We found a surprising effect on snail shell development,” said Dr Baynes. “The snail embryos grow elongated ‘banana-shaped’ shells instead of tightly curled shells”.

“This disruption to shell shape is not what we might expect in a mammal or a fish, which would be reduced male characteristics or sperm production. Our findings indicate 5αR has an essential role in snails and could lead to a better understanding of hormones and shell development in molluscs. It’s an interesting first step.”

Reported by:

Hayley Jarvis,

Media Relations

+44 (0)1895 268176

hayley.jarvis@brunel.ac.uk