For those of us that like a fairy-tale dimension to our global fandom, then it doesn’t get much more magical than being a ‘Swiftie’ (that’s a fan of Taylor Swift to you and me).

Even in the lofty context of global superstardom, 2023 has been an enchanted year for Mother (as Taylor is affectionally referred to by her fan base): Billionaire status, the record breaking (and internet-ticket-sales-busting) ‘Eras’ World Tour and accompanying film, Time Magazine Person of the Year, Forbes ‘most powerful woman in entertainment’ (not least because she contributed an estimated $5.7 billion to the US Economy), two No1 albums, and now the most streamed artist globally on Spotify. Off stage, she has used this influence, sometimes controversially, to advocate for female empowerment, promote LGBTQ rights, endorse the Democrat Party and to champion the music-ownership rights of musicians and composers.

Not unsually, Swift’s multi-faceted success rests substantially on the shoulders of her fan base, a force that shouldn’t be underestimated. If the above list seemed exhausting, then it is equally gruelling to keep up with Swift’s constantly altering celebrity text. Rather than rejecting the rebranding that comes with each music release (Hills 2018), ‘Swifties’ have actively embraced and endorsed each change. Her transformations are enacted seamlessly because Taylor can simultaneously situate herself as both a ‘hapless pop princess’ and ‘savvy industry professional’, whilst maintaining a sense of authenticity with her fans, as revealed in her compositions about heartbreak and being an outsider (Wilkinson 2018 p.441). As such, adaptability and change are seen as central aspect of her star persona that, helped by the playful interaction between Taylor and her fans about the nature and timings of these changes[1], positively contribute to her celebrity text. As Driessen (2022) wryly observes, the authenticity of her public image makes her private life and personal convictions even more controversial, particular as each is placed under the same scrutiny as her public persona by her fanbase.

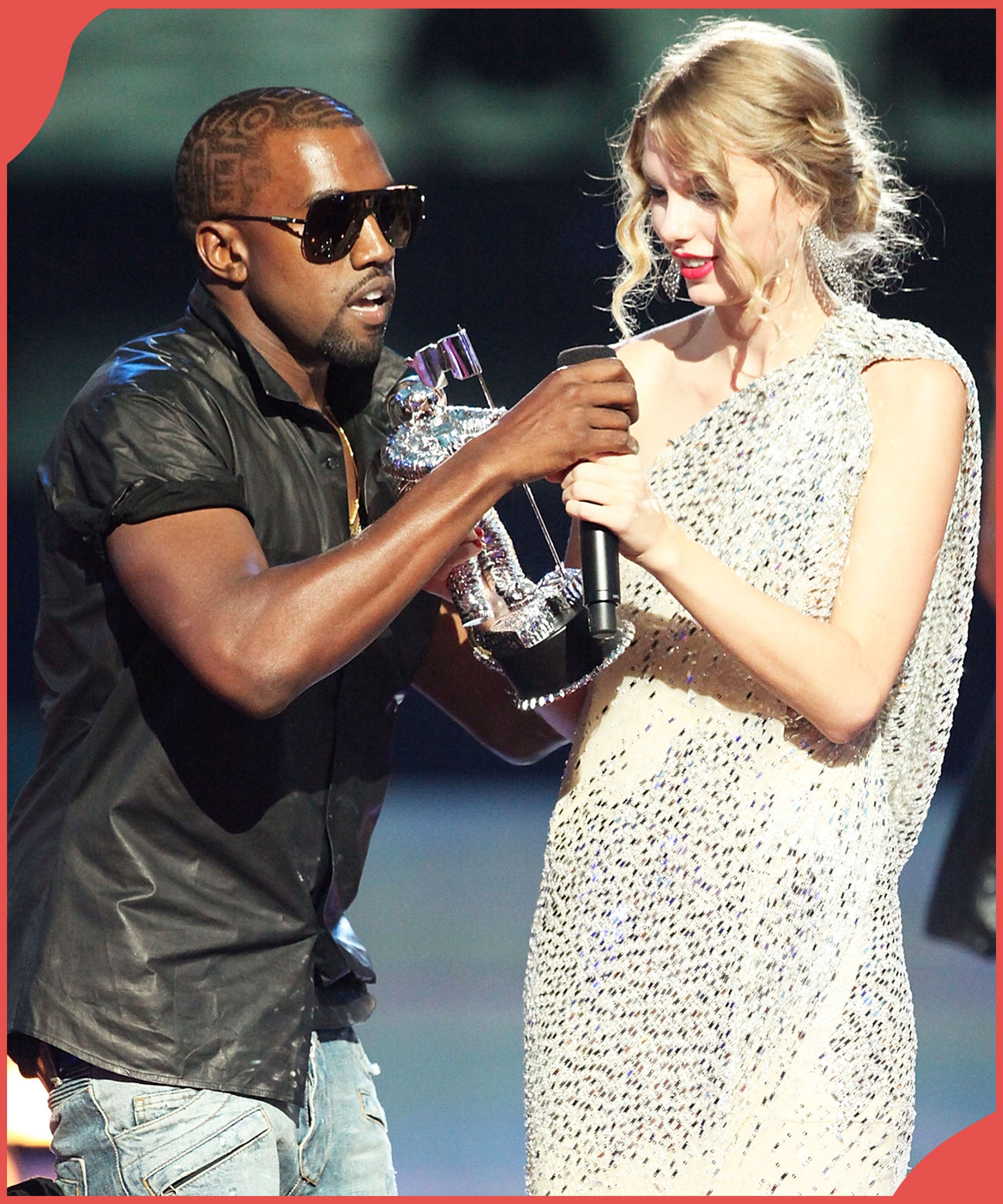

I was thinking about this interplay recently as I watched her receive nine awards at the MTV Video Music Awards (or VMA’s as they are universally known). As Taylor thanked her fans for their ‘unbelievable’ support, I cast my mind back to the 2009 awards, fourteen years earlier, which seemed to me to have been a seminal moment in this night’s success. Way back then, as Swift was about to accept her award for Best Video by a Female Artist, I recalled how Kanye West stormed the stage and shouted at her, ‘I’mma let you finish, but Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time! One of the best videos of all time!’ Now, whilst the drunken interruption of one celebrity trying to upstage another is not unusual at these sorts of awards (think Will Smith at the 2022 Oscar Ceremony) what is significant here is the way that this event cemented the on-going celebrity narrative of the two protagonists; West as a pop culture villain and Swift as a pop culture victim. More interestingly it also set a narrative that mirrored and tracked the scissions in Western Popular Culture and set the agenda for a global fan-base.

The timing of the 2009 VMAs was a significant point in Swift’s transformation process. She was transitioning from Country Starlet to fully-fledged Pop Princess. She arrived wearing a glittering silver gown in a pumpkin styled horse-drawn carriage. The imagery was clear, 19-year-old Taylor was Cinderella and the VMAs the Ball. This was to be her fairy-tale entrance into pop mainstream and West was the pantomime villain who brought it all crashing down. If this had been West’s intention, then it soured quickly. Booed by the crowd and ejected from the ceremony, he was forced to make a public apology via his blog later that night. West might have hoped it would go away, and this could well have been the case had it not been for two technological factors. Firstly, in their effort to salvage the event MTV had quickly deleted all footage of the interruption. This meant that any grainy recordings immediately gained ‘cult’ status and were hungrily sought out across the internet. Secondly, the emergent Swift fan-base (and the public who felt they had missed out on something significant) took to the fledgling Twitter service to seek out the video and exchange views. In 2009, Twitter was barely three years old, and still evolving as a platform, but the VMAs showed that it could stand out at driving conversation during a pop culture moment and could shape audience response to news coverage (Grady 2019). Twitter also facilitated celebrity input in a way that we hadn’t seen in fandom. Leaked video of President Obama calling West a ‘Jackass’ whilst describing Taylor as a perfectly nice young lady, set the subsequent agenda, as did Katy Perry likening West’s behaviour to stepping on a kitten. In this sense, as white teenage girl victim to a bullying older black man, Swift secured a growing base of righteous, enraged young women (the embryonic Swifties) who knew how to use technology to advocate for their Mother.

A year later at the 2010 VMAs, Taylor performed ’Innocent’ with images of the previous year playing behind her. Swift describes the performance as a song to West, rather than about him. Swifties were quick to see this as an act of forgiveness, and this narrative soon set the context for the future public persona of both. However, in 2016 a counternarrative began to gain traction. West released ‘Famous’ a track which references Taylor in the line ‘I made that bitch famous’. If the connection wasn’t clear, the accompanying video featured images of a naked Taylor-likeness. In the subsequent controversy, West and Swift defaulted to the positions we had seen seven years previous. Swift condemned the track, reopening the old wound of white female victim vs black male bully, and subsequently used it to endorse the authenticity of her image as a serious composer/performer who just wanted to get on with her work and please her fans. West defended himself asserting that he had sought Taylor’s blessing prior to its release, a defence that largely fell on deaf ears until his wife – Kim Kardashian-West – released a series of videos of him calling Taylor that seemed to support his claim.

Once again, technology drove the fan response. Twitter was awash with the hashtag KimExposedTaylorParty and any mention of Swift was besieged with snake emojis. Taylor countered with the claim that it was the misogyny of the word ‘bitch’ that she objected to. Whilst this played into the values of a young, mainly female fanbase, beyond the Swifties a narrative that Taylor was using the VMA saga tactically began to be popular: victimhood sells, particularly if it plays into popular cultural stereotypes. The old DW Griffiths imagery of White Womanhood preyed on by predatory Black Masculinity, dug deep into the American psyche. But by now, this narrative was being muted, socially by the Black Lives Matter movement, and creatively by the criticism of the lack of diversity in the 88th Oscar nominations. Some writers began to revisit the events of 2009, claiming this was another example of ‘Black Excellence thwarted by White Mediocracy’ (Medford 2016). Taylor could no longer sustain the claims she had made, turned her back on her fan base, and disappeared for a year. When she re-emerged in 2017, her subsequent album Reputation seemed to again reinforce the whole victim narrative (most notably ‘Look What You Made Me Do’), something that didn’t go down well with critics.

Of course, Swifties openly embraced the new Taylor, one who was unashamedly critical of those that didn’t like her. This felt like a message of rebirth and empowerment (in her run up to the release Swift had symbolically deleted all her social media posts, replacing them with the same snake emoji that had been levelled at her). Fans felt equally empowered, not just by the lyrics, but her clever reclaiming of the snake emoji. Social media posts at the time talk of the ways she offered them a blueprint in how to face the World, a theme which continued with the release of her follow up Lover, 2022’s Midnights and most recently in their defence of her enthusiastic support for the Kansas City Chiefs (her latest boyfriend, Travis Kelche, is a star player). In contrast Reputation album sales (and accompanying lucrative World Tour) did little to diffuse the criticism that Taylor courted controversy for her own ends, this was white hegemony being played out before our eyes.

But if racial landscapes had changed, so had gender politics, and, post Trump, Politics more broadly. To support Mother, many Swifties focused on gender, claiming that the both the 2009 and 2016 attacks were a criticism of young female artists creating art for young female audiences – the ‘authenticity’ narrative that Swift had adopted in the intervening years. This caring authenticity, seemingly focused on the interests of young women, and her subsequent endorsement of the Democrats in 2018 in which she offered a critique of discrimination more generally, cemented a move from ‘celebrity’ to ‘political celebrity’. She was no longer ‘authentic’ because she sang about the things her fans were familiar with – love, heartbreak, being an outsider – now she offered political influence, a voice to those that felt politically dispossessed (a theme emphasised in the 2020 releases Folklore and Evermore).

As I contrasted the two award ceremonies, and Swift’s transformation(s) over the intervening years, I was struck how the power of the celebrity, their fandom, and the interplay between the two, appeared as an important modern fairy-tale. Like folk tales, celebrities are emblemic in the sense that they are fantasies onto whom we project values and beliefs, particularly in terms of what they do and what they say. As Bruno Bettelheim (1976) reminds us, such tales are important cultural devices that offer us opportunities to develop a greater sense of meaning and purpose about our own lives. Similarly, Gerard Jones (2002) cleverly observes that Fantasy allows us to explore what we can never be in real life. Cultural moments like the 2009 VMAs offer us a symbolic critique of wider notions of Race, Gender and who might be the acceptable voice of such things in the popular cultural sphere. These spaces and moments are often claimed by young people, which in turn leads to the authenticity of the actors within and the righteousness of the various fan bases operating around them. The Swifties continued fannish investment in their Mother, despite criticism and controversy, reminds us that fanspace is in someways a resistive space, and that authenticity in this environment is moral as well as political. The Taylor that stood before us at the 2023 VMAs had changed, she seemed less Cinderella and more like Elsa, proudly proclaiming that she had let it go and that ‘the (political) cold never bothered me anyway’….

References

- Bettelheim, B. (1976). The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Knopf, New York.

- Driessen, S. (2022) Look what you made them do: understanding fans’ affective responses to Taylor Swift’s political coming-out, Celebrity Studies, 13:1, 93-96, DOI: 10.1080/19392397.2021.2023851

- Grady, C (2019) How the Taylor Swift-Kanye West VMAs scandal became a perfect American morality tale, Vox, available at https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/8/26/20828559/taylor-swift-kanye-west-2009-mtv-vmas-explained

- Hills, M., 2018. An extended foreword: from fan doxa to toxic fan practices? Participations: journal of audience and reception studies, 15 (1), 105–126.

- Jones, Gerard. (2002) Killing Monsters: Why Children Need Fantasy, Super Heroes, and Make-Believe Violence, New York: Basic Books/Perseus.

- Medford, G. (2016) Criticizing Taylor Swift Isn't About Negativity Towards Successful Women, It’s About Vindication, Vice, available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/689zw5/taylor-swift-kanye-west-famous-phone-call

- Wilkinson, M., 2019. Taylor Swift: the hardest working, zaniest girl in show business . . .. Celebrity studies, 10 (3), 441–444. doi:10.1080/19392397.2019.1630160

- [1] One example of the complexity of this ‘game’: On her Eras Tour, Swift dons a T-Shirt similar to the one she wore in the music video for ‘22’ which spelt out ‘Not a lot going on at the moment’ a phrase that came to foretell the surprise release of the albums Folklore and Evermore. On the first night in March, the shirt was re-written to read ‘Alot going on at the moment’ with ‘Alot’ highlighted in bright red. The next night, the shirt coined the phrase ‘Who is Taylor Swift anyway EW!’, this time ‘EW’ was emphasised. Online there was much speculation that the highlighted letters were an anagram of ‘Speak Now (Taylors Version)’ and that this was a hint of its immanent release (it was eventually released in July).